It is 35 years now since the Piper Alpha accident took the lives of 167 men who had been working on the platform operated by Occidental. I don’t think that I can ever forget the numbers who died or the events prior to or after that dreadful event. It was one of those career defining moments that some journalists hopefully never experience as it would have traumatised them along with many of those working in the offshore sector and, of course, the families of the workers who perished.

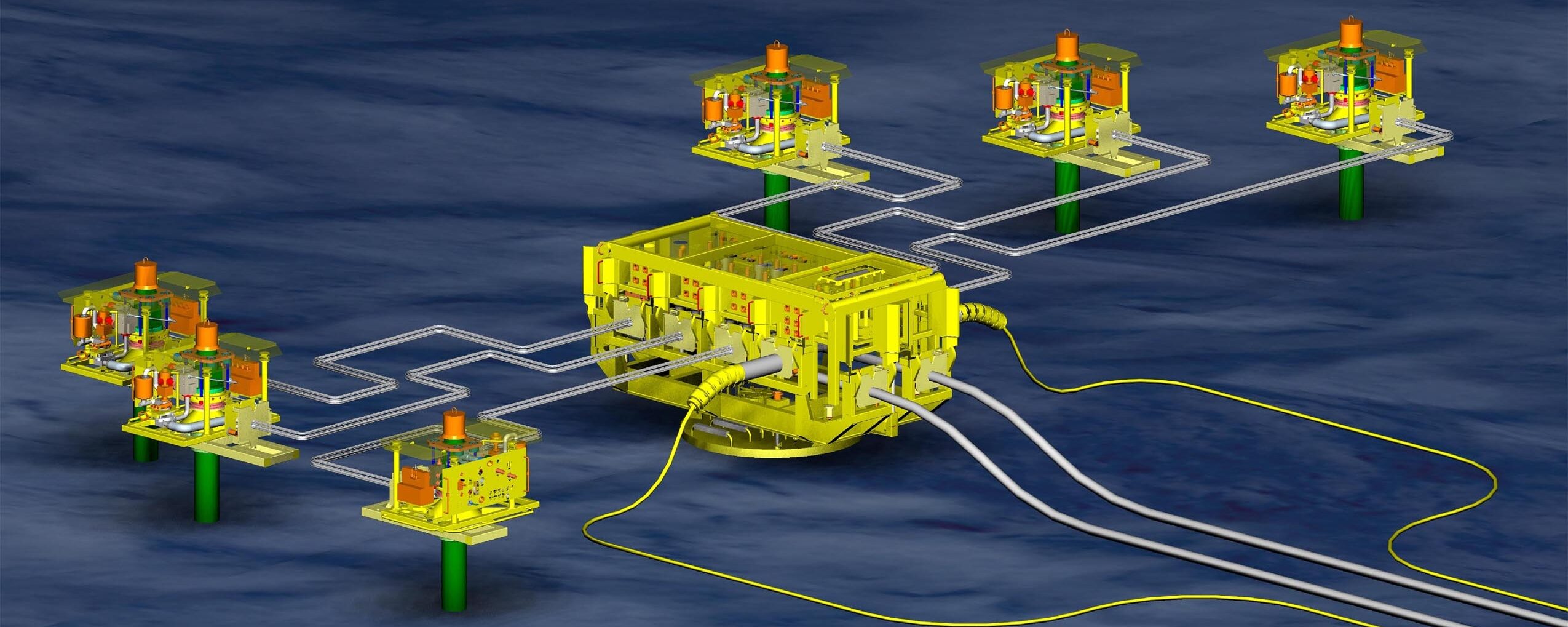

Personally it was unfortunately one of the highlights of my journalistic and business careers. As a so-called ‘expert’ on the offshore sector, I was asked to write articles that appeared in the The Times and New Scientist, I was on breakfast television with Jeremy Paxman and Kirsty Wark and on radio on the World at One. A year after the event in the aftermath of the Cullen Enquiry, I organised the first of two seminars on the development of subsea emergency shutdown systems (SESS), a technology necessity that was mandated to prevent another such tragic accident.

Many readers will know the name of the event without knowing the details. To summarise, an explosion on board the platform set off a horrific chain of events: a ruptured gas riser bringing gas by pipeline from another platform fed a fire that eventually consumed and destroyed most of the topside of the platform; those trying to escape either could not get to lifeboats or could not launch them and many of those who did found themselves swept back under the platform due to the sea conditions. The fire burned for days before well experts from the US were able to cap all of the wells and the gas – in a pipeline more than 20 miles long – finally stopped flowing.

The Cullen Enquiry was scathing about the safety standards at Piper Alpha specifically and the industry as a whole which resulted in a new approach to safe operations. The technology upshot involved new types and applications of control systems and in valves and new designs and operations of lifeboats. The use of SESS within the 500m safety zone around platforms became standard around the world as it became evident that the major impact on the whole event came not from the initial explosion, but the uncontrolled flow of gas that fed the fire and eventually destroyed the platform.

The industry as a whole hoped that this would be the last catastrophe to tar it, but it was not to be. Two decades later the Deepwater Horizon/Macondo proved to be a worse event, at least as far as how the environment was affected. The industry, particularly the drilling side, was incredulous at this accident. One driller from a very big company told me without any concern about attribution, ‘we didn’t think that this could happen’ when triple redundant blowout preventers were the norm. Alas it could.

The question remains, has the offshore oil and gas industry learned from these two catastrophic events within just over three decades. It is hard to know. Whether the commonplace minor accidents and spills has been reduced awaits data from the UK Health & Safety Executive. What is worrying in the UK, for example, is that the sector is now populated by more new small companies at any time since back in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Can such organisations deal with the difficult decisions to be made at the time of an accident? This is a valid question, although the big companies have not covered themselves in glory at the time of lesser events. We can only hope that another such tragedy is not on the horizon, no pun intended.

**********

On a less serious note and in the spirit of the energy transition, if you believe that wind turbines are beautiful objects, then you might check out a screenprint, In Praise of Wind, by Andy Lovell at www.andylovell.co.uk. It was produced for a collaborative show between Gloucestershire Print Co-op and a similar Swedish group.