After venturing recently somewhat off piste, I thought I would return to the heart of the matter – subsea engineering. It is quite interesting how quickly some technology innovations and ideas have gone from the realm of the Grimm Brothers, ie fairy tales, to mainstream thinking.

To wit, Chariot Oil & Gas – that well known (!) operator with lots (!) of subsea experience – has been evaluating its Anchois gas find, about 40km off the Moroccoan coast in just under 400m of water. The reserves are not enormous. Any development would be based on 300bcf in the first instance with another 100+bcf that could be added easily and some other nearby finds that could add up to possibly 1tcf. Considering that just the other day PTTEP made a find off Indonesia of at least 2tcf, this remains a moderate prospect, although it could be important in the context of the Morrocan energy scene as a feeder for a power plant that is currently being fed by coal and oil.

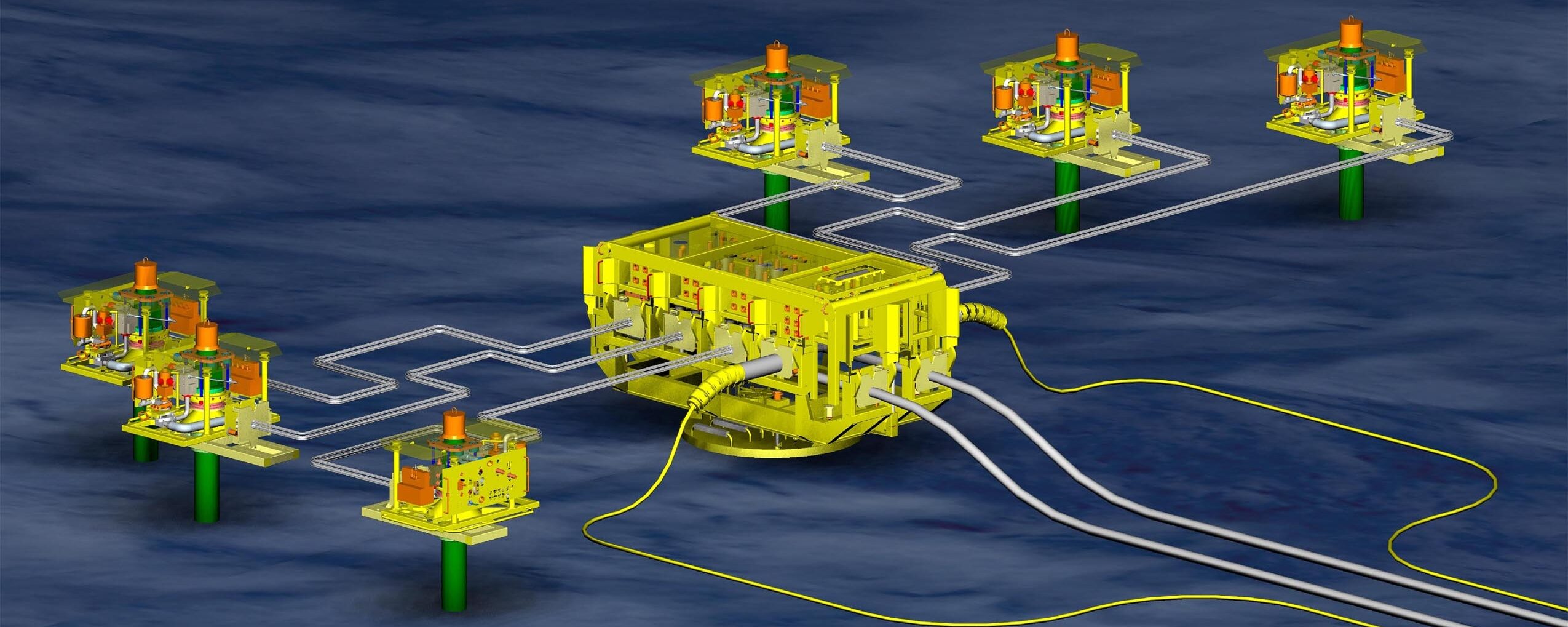

Anyway what I found of interest is that Chariot rather nonchalantly has talked about a ‘subsea-to-shore’ concept based on ‘proven industry standard technical solutions and equipment’. Wow. I hadn’t realised that subsea-to-shore was in any way standard. I decided to try to remind myself of how many such project there have been. We begin with Snohvit and Ormen Lange in Norway and then add in a bunch of projects off Egypt, some by BG and some by BP, and there is Total’s Laggan-Tormore in the UK. I struggled to remember any others, although there might be another that my ageing brain has forgotten.

I suspect that Chariot has looked at what has been done off Egypt – at West Delta Deep Marine and the BP finds at Rosetta et al – and thought it could do that. I am not saying that it can not. But just remembering the challenges associated with all of these projects, particularly the pair off Norway, it might be a bit casual to consider any subsea-to-shore concept standard. The production equipment side might not be very challenging, but the shore approach and pipelining might be more so. We watch with considerable interest.

***************************************************************************************

Another recent project announcement – for Anadarko’s Mozambican deepwater gas-to-LNG development – mentioned in passing that the subsea hardware award was a continuation of a 25 year relationship between Anadarko and FMC, now TechnipFMC. That is quite a good run and rather good biz for FMC. I recall an OTC presentation by the US indy, recently acquired by Occidental after Chevron took a shot, in which one of its senior engineers said, to paraphrase, that every time it had need of subsea equipment, it went to FMC and said encore, please, or rather we will have what we had last time. That might be a simplification, but probably not far from the truth.

There is rather more to this story than meets the eye. If one ventures back 25 years, it was a time when the subsea hardware market was much more balanced with Vetco and Cameron looking more like equal participants in the bidding game. It would also be around the time that Shell was developing the Mensa deepwater gas tieback. For those with long memories, they might recall the debacle surrounding the so-called split xmas tree which separated early on after deployment and had to be retrieved. It might not have seemed to be a great time for FMC, but look what happened afterwards.

Shell US never took the split tree failure as a typical hardware incident and continued to give FMC most – and maybe all – of its subsea hardware contracts. Anadarko had a long series of projects that also went to the FMC and Statoil also began doling out a significant portion of its contracts to the company as well as I believe did Woodside. So it might well be around that time that FMC stretched its lead over its competitors to be the clear market leader for what now seems like decades.

***************************************************************************************

Don’t know how many of you have seen the documentary ‘Last Breath’ on Netflix. It was quite fixating – the story of how back in 2012 a North Sea diver (Chris Lemons) found himself stranded on the sea bottom after the dsv Topaz lost its dynamic positioning system and his umbilical was torn away. He survived at least 30 minutes in 100m of water despite, in theory, having no more than five minutes of oxygen in his emergency tanks.

While watching this drama unfold – some of the images were original and some were dramatised while the interviews were contemporary – and being a journalist at heart, my mind immediately raced ahead to issues that popped in my head. The first – which has a bit of context with the Deepwater Horizon accident – was how a triple redundant computer system totally failed, leaving the vessel floundering in the water and putting a man’s life at risk. It was the same point discussed by Bil Loth and myself vis a vis Deepwater Horizon as we were in Houston preparing for one of our subsea engineering courses just prior to OTC. This was a triple redundant bop system – how could it totally fail?

The second issue came to mind after watching the dsv crew do a hard reset of the computer network and was able to get the DP system back on line. It launched its rov to try to find the diver, but did not know exactly where to look. I immediately thought ‘doesn’t the diver have some sort of beacon or transponder so he could be located ASAP?’ Obviously not.

So the questions now to be asked seven years later are: have DP systems been improved so that a catastrophic computer failure can not occur and do divers now have some sort of location device so that they could be found if, God forbid, they became detached from their systems underwater. Certainly much has has happened with bop systems in the aftermath of the drilling catastrophe. It would be good to know what, if anything, has happened with these other two issues.

11 thoughts on “No big deal? What?”

Ironically from what I recall having watched “Last Breath” and the formal in house documentary, Chris Lemons Umbilical appeared to get trapped on a Clamp On Transponder Bucket , which are for structure installation purposes and normally recovered once complete.

Maybe we should consider a flush mounted permanent bucket that can be used for the purpose you suggest.

However the coordinates of the structure must have been known to carry out the job in the first place.

Am I correct in assuming that Bibby Offshore was running Topaz at that time?

Shore approach … always a solution , tunnel ? Or drill a long horizontal directional well from shore and connect the flow line at the end of it ? Via a vertical one . Always find it interesting that the piles supporting the trans Alaskan pipeline above ground are kept individually frozen in the permafrost , meanwhile the animals can migrate under it with no problems.

JJD – good to see that you still have something to say.

“A triple redundant BOP … “ as long as the failure of No 1 is erased completely before activating No2 and that errors /failures of No 1 & 2 are completely erased before initiating the last resort being No3 . Easy to say, when panic steps in and the various remote control units in the early phase of a blow out . Other part of the system may have suffered mechanical / hydraulic failure irrespective of the electronic command on surface alone , the subsea part of it by underwater acoustic control is another level.

We had identified similar hydraulic locks in early North Sea BOP (1970) when simply switching from Yellow pod to blue pod became locked ? Simple ? Not when you are you are in a panic situation.

With all that software available , you often need the one you have not got ! Or insufficient testing program is often the source of the disaster in most subsea applications.

Another “subsea to shore” example is ONGC’s Vashishta / S1 development (East Coast India).

thanks for that.

… and Corrib? (although I never seem to be able to establish that project’s status)

On your Subsea to Shore comments, not long ago I was asked for advice regarding a similar project offshore Africa. It was indeed the approach-to-shore aspect that had potential issues – in this case where some equipment materials compatibility/lifetime assumptions had been based on subsea conditions; temperatures in shallow water and on the beach in Africa tend to be much higher than those in mid to deepwater. Do the right questions get asked of the right people?

Isn’t that always the issue – who knows about what and who remembers what has been done before?

….and understands why it was done like it was, before introducing some “smart improvement” that brings unintended consequences.