When I gave the last blog this title, it did not occur to me that I would start stirring up memories, even if mostly very good ones.

What I received – a comment available for all to read – was a very heartfelt missive from the estimable Ian Ball. I think that whenever one decides to depart – whether a position or this earth – one has to mull over things from the past which are usually somewhat bittersweet. Fortunately, Ian is simply hanging up his ‘subsea’ boots to enjoy some time ‘up north’ without anymore biz trips to India or even to Aberdeen.

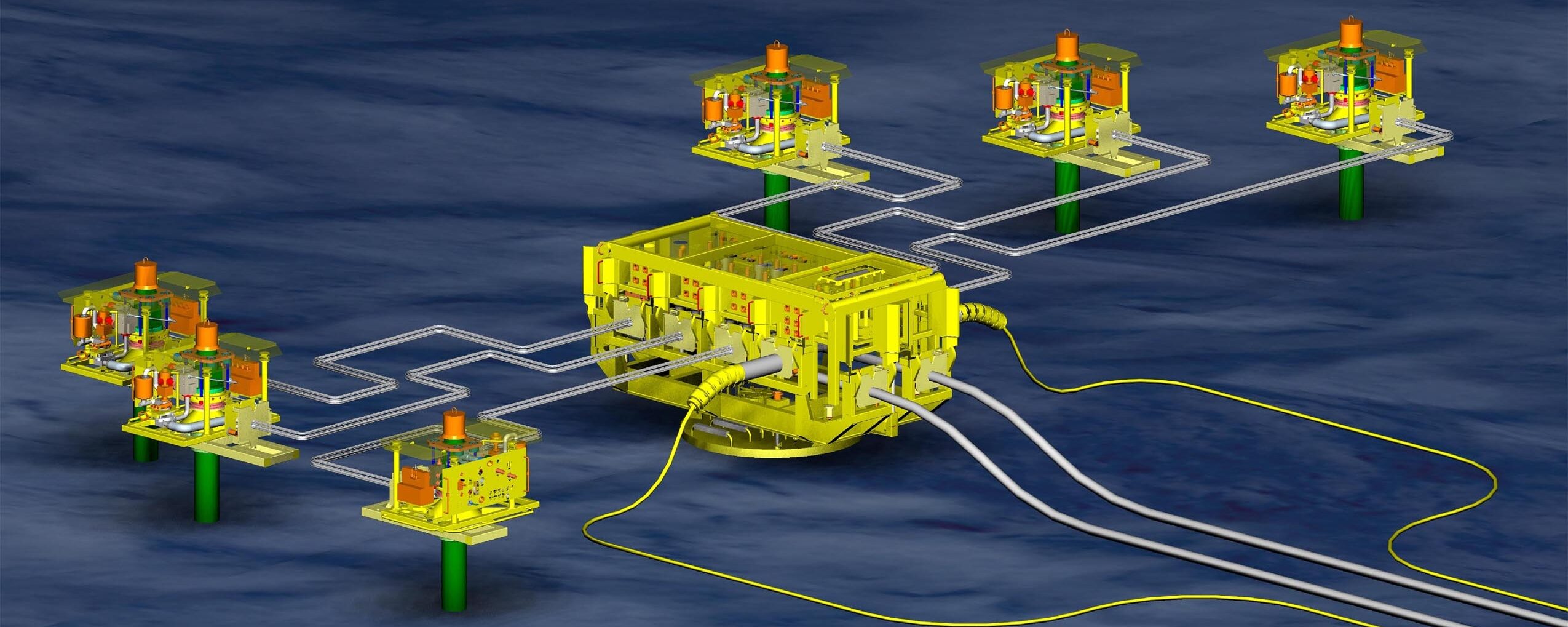

My entry into the subsea world (circa 1984) was post-UMC, so I did not know Ian during his early time with Shell. I first encountered him after he had been seconded to Norsk Hydro and was working on the TOGI team. What a great time that was. Operators, to be honest mostly Norwegians, had the time, money and enthusiasm to embark on epic projects without the expectation or assurance that the ideas would work. Just consider the challenges that confronted the Troll Oseberg Gas Injection project which aimed to bring gas from a reservoir on the western fringe of the giant Troll structure to support oil production from the main Oseberg reservoir. The water depth was just over 300m – there had been no production in the North Sea even beyond 200m at that time (Magnus at 185m?) – with a proposed tieback distance of 48km. These depths and distances are no longer seen as quite so daunting, but they were game-stoppers back then.

Just consider what had to be tested and proven before the project could even get started: installation of trees in North Sea conditions in waters beyond what had been done before; remote pull-in of the largest pipe (20in) installed to date in such waters; and the development and testing of a control system for the longest subsea tieback ever attempted, amongst other issues. It was a project that devoured money and engineering prowess for the better part of a decade before it came onstream in 1992. I know – because Ian told me – that probably the biggest disappointment of his career was not to be appointed project manager on TOGI – it had to be a Norwegian because that was the way things were.

Ian came back to the UK and there were more challenges to come. He got to be Shell’s man on Foinaven, in its own way a historic project even if there were some major screw-ups enroute – 400m water depth, special steel manifolds, an fpso that was cut in half with a new mid-section installed, et al, in an environment West of Shetlands that was more extreme than even the North Sea.

And then later, there was his relationships in India where he assisted Reliance in getting India’s first deepwater subsea system in the water. Quite a CV. Hey mate, the next pint is on me.

***************************************************************************************

Speaking of the North Sea and deepwater, things are moving on and down. In Norway, Equinor announced first production at Snefrid North, a subsea satellite to the Asta Hansteen gas production spar, in 1,309m.

Back over on our side of the median line, Siccar Point Energy is revving up the West of Shetlands Cambo prospect, inherited from OMV, in 1,100m. Singapore yard Sembcorp Marine which owns the intellectual rights to the Sevan Marine circular fpso designs has picked up the front-end work for the floater for this project and is said to be the favourite to build it as well. I think I saw that BHGE is doing the subsea side.

***************************************************************************************

So what came out of Offshore Europe, besides the introduction of the spanking new P&J Live events centre? At least there should be no more boiling hot tents or leaking roofs.

Let’s start with the lingo: if data and digital are not in your vocabulary, you might as well be using esperanto. It seems like the oil business is no longer about dirty hands and, who knows, it might never be again. To wit, how is AI going to change the offshore world? Robots plus drones plus digital tools will provide a new approach to inspection and equipment integrity. Look ma, no hands!

And how will this manifest itself? How about a digital twin? That is, a virtual model of a physical asset which evolves to reflect changes to the operational status and integrity of the equipment. Now this is interesting as it could result in a reliability approach suggested years ago, ie replace mean time to failure or between failures (MTTF/MTBF) to MFOP or maintenance free operating period which would allow equipment to be replaced before it fails. That is, unless whoever is in charge says ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t replace it.’ Hmm.

Is the oil biz filled with dinosaurs? It could be (see above) and Total headman Patrick Pouyanne fears it could get worse unless there is some new thinking very fast.

Question: what happens when you try to put one of the new generation super-heavy BOP stacks on a legacy wellhead? Could be ugly with all remaining fatigue life going in a flash. Trendsetter Vulcan Offshore has developed a Wellhead Fatigue Mitigation System based around a lightweight tethered BOP. It could be used for exploration wells, but more likely for re-entry and P&A work on older wells.

And what’s happening in the subsea world? It’s still about savings as it has been for more than four years now. Aker Solutions’ ‘intelligent subsea’ ( who ever said subsea was stupid?) aims to reduce engineering hours by 70% using automated designs. Sounds great for the client, not so good for the engineering personnel. As for BHGE’s Subsea Connect, it says it will reduce life of field development costs by 30% using its new Aptara line in equipment which includes a lightweight compact tree and compact block manifold.

***************************************************************************************

I just would like to apologise to anyone who hoped to see me last week in Aberdeen. Hoping to make some money next year which might get me to Stavanger or even to Houston for OTC. Taking a break now for a couple of weeks. Back in early October.

3 thoughts on “LIFE AFTER OFFSHORE EUROPE: PART II”

Ian Ball ‘s contribution to the subsea industry at meetings, tech papers and seminars was always an eye opener , it pointed the way to leadership ! on a tech basis a challenging guy, no so sure about the political side of it after all we are representing the people who pay the salary ! Best of luck to Ian and his undertakings up North, mountains are a good place to see the world above water line. But there is always time for a pint ….

I am battling my way thru the Data Protection syndrome, who is protected the company collecting the data or the guy giving infos over the phone ? Better work subsea ….

Hi Steve – I’ll even be happy to travel down to Cheltenham one day to celebrate with you all sorts of high and low milestones over 5 decades from the 1968 beginnings over that pint – and the rest.

Before I do that though, I feel honour-bound to step in with a little more of the traditional “Sasanow slant” to your article, than you were so uncharacteristically polite to do yourself. Incidentally, I advise any reader with any degree of attention deficit disorder to look away from these ramblings now. I’ve left it a couple of weeks to see if anyone else might be bold enough to do that for us, so on balance I offer sincere thanks to all of you who bit your tongue! One can generally though rely on the highly esteemed John Daeschler to avoid holding back on his fascinating observations. Sure enough, my heartfelt thanks go to John for reminding us that I have not always been averse to rocking the boat a bit when it seemed like a potentially dangerous complacency may be pulling the wool over our eyes, or rendering a conference to become overly dry and dumbed down. He calls that a “political” characteristic. I always intended it simply to be a constructive thought provoker. (Don’t even mention Brexit to me!!)

It’s absolutely true that one of the great highlights for me was being able to be a part of that wonderfully innovative and bold TOGI team in the late ‘80’s. I actually had to quit Shell to do that, but in 1985, the first big oil-price downturn had made that hitherto unthinkable action a little more feasible. My first task within Hydro was a formal review of their Oseberg plans to create a harsh-environment production test FPSO to be called “Petrojarl-1”. It was also to have its own subsea tree, hanger, riser and connectors, and I dutifully highlighted all the issues and risks involved. My second task followed all too quickly, namely managing all those identified risks into a successful delivery of Petrojarl-1 conversion in just 12 months flat! That was a real stretch for me, and I couldn’t believe how I fell into that trap! That’s when I set in stone my previous impressions of what immense value to the industry constructive collaboration really is (in this case with Golar-Nor). I rejoined Shell in Aberdeen in 1990.

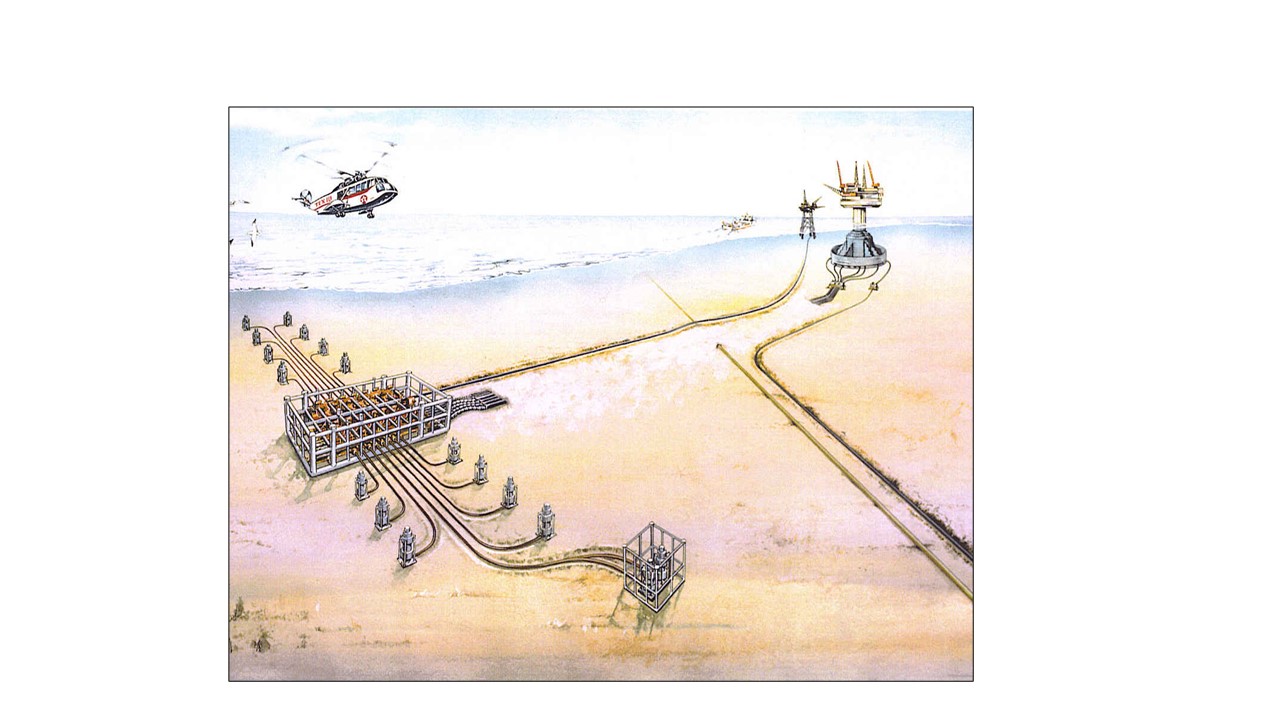

My initial collaboration exposure had actually occurred 10 years earlier, when in 1974 I was tasked with delivering Shell’s first subsea tie-back technology pilot to the planned 1976 Brent-Bravo concrete platform (since decommissioned). Shell had truly inspirational technology leaders and teams in both The Hague and USA at the time, and Brent-7 was to incorporate for testing as many of their new-fangled technologies as possible to pave the way for future larger-bore production cost reductions. This included through flowline (TFL – not Transport for London!) circulation of 4” downhole maintenance tools (3” had been the maximum bore tested to date). The particular collaboration of note was with a certain infamous Coflexip outfit, to create a larger-bore flexible flowline installation vessel for harsh environments, ultimately to be called Flexservice-1. This was going to be needed for a first-end pull-in/connection at the Brent-7 tree, and a layback to the Brent-B j-tube pull-in.

It’s a long-involved story, but suffice it to say that the operation (to deliver a successful hi-tech pilot installation to production in 1976) was a great success – even though the patient (sustained production) ultimately died! We managed to get the first production congratulatory telex (remember those?) back from shore to where I was based on the platform, just before the TFL standing valve ball cage in the upper completion shattered under the monster Brent flow conditions, and back-checked in the upper tubing as solid as a rock! It was never deemed cost-effective to re-enter that well for repair, once the massive platform wells themselves were coming online fast and furious.

Whilst still reeling from that sobering experience, I was tasked in 1978 with installing another technology pilot on the equator in Brunei – would you believe a subsea tree system that could cope safely with being scraped off the seabed by an iceberg! That one did end up producing sustainably, albeit with the reduced 3” TFL tubing. However, it did prove more problematic to do a convincing test to demonstrate its ability to deal safely with real-life iceberg scour!

So there we are Steve, I’ve finally fessed up with just an inkling of what went on before your arrival on the scene, and feel all the better, if a little more thirsty, for it. Now it’s just a question of us arranging exactly where and when you get that first reflective pint on the table. Thanks mate, hope you’ve had a good break, and thanks again so much to all subsea friends across the whole industry who’ve tolerated and humoured me so obligingly over so many decades. It’s all been so very rewarding and ever so much appreciated. Best wishes for similar outcomes to all still carrying the batons forward in the much-changed but still as challenging a subsea world.

John JL Daeschler

With a lot of convincing we purchased and laid a 4 ” Coflexip in 1979 in the Argyll field North Sea took 8 hours connected each end by divers. Because the product was sold on the basis of being easy to install , our response was that we would install it ourselves. We rented the 70 tons winch reel from Coflexip in Le trait and installed it on a Smitt LLoyd supply boat wood deck !

The early scope of Coflexip was to produce a flexible 5 K hose 3″ 12 ft long to replace articulated kill and choke lines and cementing manifold ect .. the dedicated fabrication and testing was a great achievment after many failures , but this is what research is all about , the technology , personnel and tooling derived from cable manufacturing ,a lot of support from Technip / IFP institut Francais des petroles and ELF in Pau and others early 1970, the 3″Dia x 12 ft line grew into the most interesting technical break for the subsea production industry, static , dynamic and sizes and pressure …

In 1992 we repaired a Coflexip flowline subsea in 140 m water depth in the Mobil Beryl field , again innovation was key considering the product we had to deal with.

There is always some fun subsea, as long as plan B, and often C have been fully tested and equipt available.