When I was editor of Subsea Engineering News, readers often asked how I managed to gather so much information. It was a matter of effort – making contacts, lots of phone calls, endless schmoozing at conferences and generally putting in the time. It wasn’t easy, but why should it have been.

That is why I am so glad not to be doing it any more. Besides the fact that I am the wrong side of 65 – but the right side of 70! – and that amount of work is a young person’s game, it has become very difficult to get answers to even simple questions these days. Firstly the number of engineers from operators who frequent conferences has reduced dramatically, so that making contacts who might answer a question directly has shrunk, leaving one at the mercy of press officers or, even worse, PR advisers.

The last blog was a perfect example. Parkmead was almost obstructive before answering a few queries on Platypus, but I did manage to finally get an answer out of them 10 days after asking. Even TechnipFMC which has always been one of the more open companies on the contracting side took more than a week to answer some rather uncontroversial query on 20K equipment development. Oh dear. Imagine if I had a real deadline to meet. I would have been tearing my hair out. At least I still have some.

One of the most protracted of info gathering exercises of my career goes back nearly 30 years ago. I believe it was 1991 when Chevron began executing what was known as the Ninian Third Party Project – the tieback of three new subsea fields, operated by three different companies, to the Ninian complex involving at least two platforms. To be fair to Chevron, it was one of the first big brownfield developments involving subsea tiebacks, but the management failed to grasp the complexity of the work and rather than having a dedicated project team with a project director or even a project manager, they simply put it into its summer maintenance programme. Wrong!

Around this time, I happened to be at a oilfield social event on a Friday just after publishing an issue of SEN. I ran into someone I knew who was the project rep from one of the smaller partners involved in the NTPP. This fellow came over to me and said – and this is not verbatim – ‘Chevron is screwing up this project big time. We have only just started and they are already six months behind schedule and £100mn over budget.’ The words may not be exact, but the sentiment and the facts were true.

I had the weekend to mull over this info and called Chevron on Monday morning. When I posed a question on the project to a senior press officer what I first got was deathly silence, followed by ‘we were wondering when someone would find out.’ He then said that he would have to go to senior management to get a formal reply. The rest of that week went by and it was nearly to my deadline on the following Thursday morning – 11 days later – that Chevron finally admitted to the problems and provided a statement on the project. A fortnight later the operator annnounced that it was pulling the project manager off another ongoing big project – Alba – to take over running NTPP. It was one of the best scoops of my oilfield journalistic career. It was so good that one of my competitors actually acknowledged that the story first appeared in SEN. That was a big deal as publications were well known for nicking other people’s stories without attribution.

Anyway the whole point of this is tale is that journalism is not the easy ride that many people think. Occasionally we get stuffed, but equally sometimes the effort and wait is worth it.

***********************************************************************************

The oilfield business has long been real-life version of the Pac-man video game, for those who can remember what that was. This company swallowed up that company and another company swallowed up that company, ad infinitum.

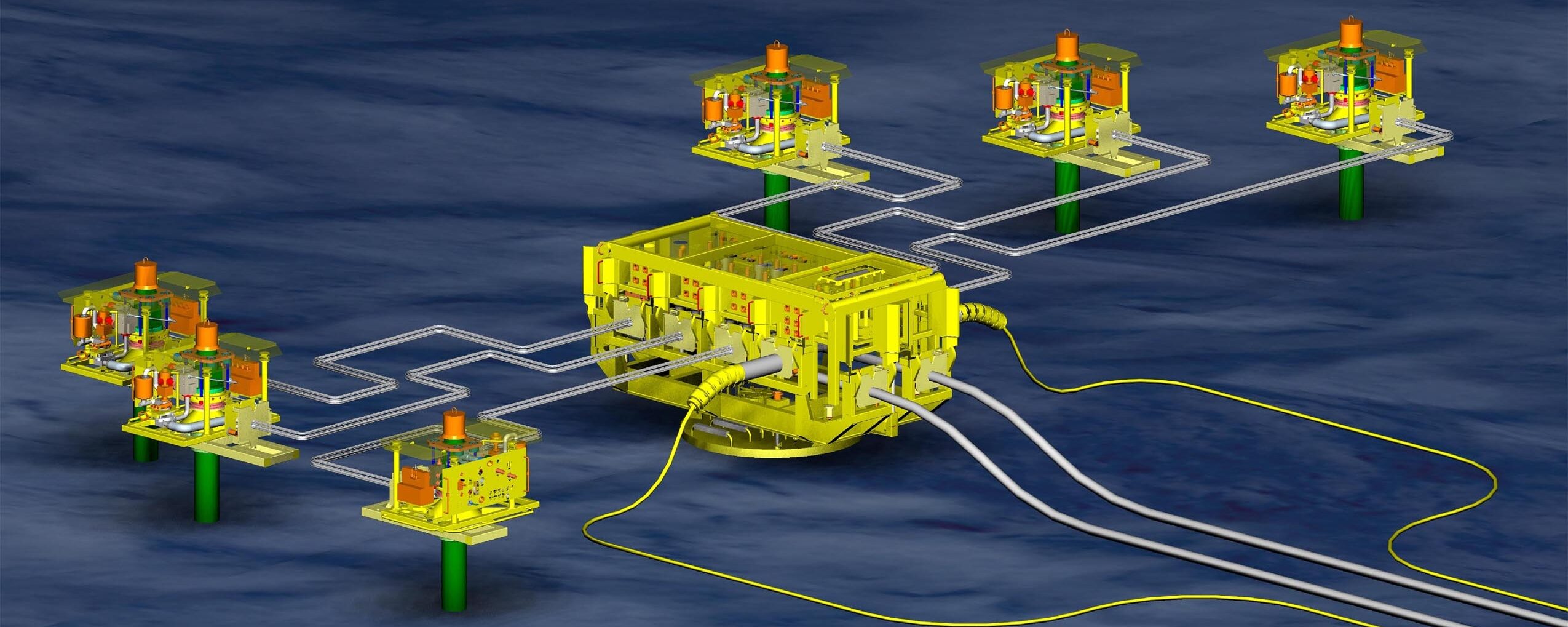

This trend came to mind last week with the announcement by Schlumberger that its subsidiary OneSubsea, nee Cameron, had won the prestigious contract to supply the subsea gas compression system for Norske Shell’s Ormen Lange project. Somewhere deep within the recesses of those companies remains the heart of Framo Engineering which is where all of the work on this technology first began. So cheers to all of you in Bergen. You have not been forgotten.

***********************************************************************************

And finally…for decades, operators have been flagging the need to do more engineering upfront (FEED) in order to ensure that field development concepts and designs can be be honed before final investment decisions, ie FID to most people, are made. This is nothing new. So what has the UK’s Oil & Gas Authority said in its report released this week on capital projects’ performance? What the industry needs to focus on is front-end loading. Thanks for that bit of insight. By the way, project execution has actually improved here – 60% of projects begun in 2017-18 have been completed on time compared with just 25% (!) before 2017. Not really sure that this is something to cheer about.

Here is something else that is new – NOT! – ILX or infrastructure led exploration. All you have to do is give something a new name or catchy acronym and it becomes the next great thing. So ILX is the new big thing in the Gulf of Mexico except that it isn’t.