In the classic late 1960’s film The Graduate, a friend of the father of the eponymous hero, played by Dustin Hoffman, tells him if he has one word of advice for him it is ‘plastics’. ‘There is a great future in plastics’, Benjamin Braddock is told, a line said with straightforward honesty, but actually meant to refer to the unnatural and synthetic nature of American culture at that time.

Even director Mike Nichols and writers Buck Henry and Charles Webb could never have realised how significant the negative allusion of that statement would become. Plastics, the first of which, Bakelite, was invented in the USA at the beginning of the 20th century, would become synonymous with the ‘throw-away’ American way of life. Now it is seen as the ultimate evil invention of capitalism, polluting our waters, killing various sea and land-based fauna and creating gigantic rubbish piles on land and in the oceans around the world.

Plastics, like many labour-saving products and materials that emerged or grew exponentially in the post-World War II era, was not meant to be some poisonous product. It was meant to be cheaper, lighter and easier to use than what had come before. The fact that this range of hydrocarbon-based materials has become so ubiquitous would probably surprise – maybe – their inventors. Likewise humanity’s inability to come to terms with how to use these products without despoiling the environment would be equally shocking.

The reason this subject has come into my mind is the result of an afternoon (yesterday) spent in Gloucester Royal Hospital’s day medical unit undergoing an iron infusion in advance of surgery (bowel) on Friday. I was observing a scene that likely takes place every day. There were eight to 10 people at a time having various types of fluids being slowly absorbed into their bodies. This was not what was interesting, but the aftermath. At the end of each treatment, various bags, tubes, clips, cannulae, et al, were disposed of in special waste containers. I thought to myself, if there were no range of plastics, both soft and hard, available to make such products widespread and antiseptic, how would or could such a department function in a way not to result in the death of many of these patients?

I am aware that there has been a great deal of work already done in developing non-oil-based products to replace some of those which have become the scourge of the rubbish and recycling industries and thus the environment. I would suspect that most of those products are ones seen by the general public which makes them feel better about our ongoing rubbish crisis. But I doubt – although I would be happy to be corrected – that much work has gone into finding new base materials to be used in the manufacture of all of these medical devices. If this is the case, then we will be needing oil for a very long time yet.

**********

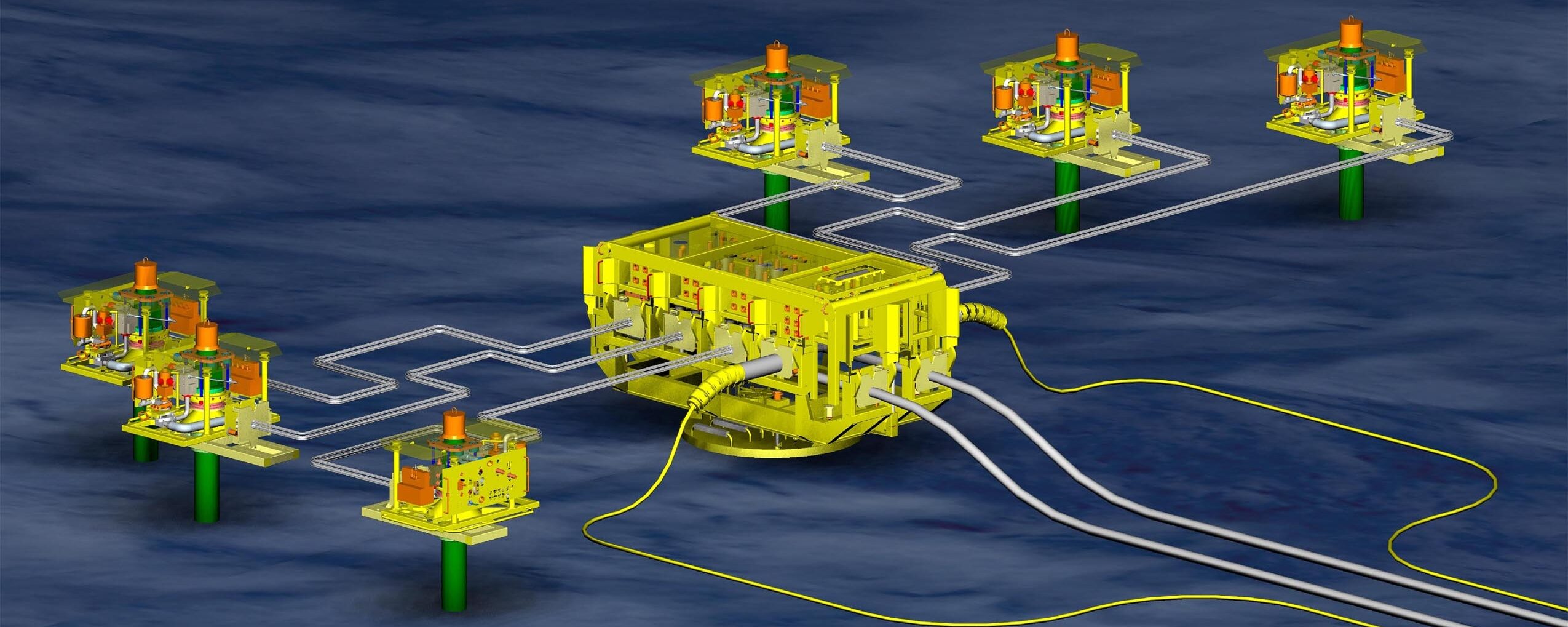

I recently wrote about Chevron’s planned departure from the UK North Sea. The egresses continue. TotalEnergies is selling its stake in its deepwater gas assets west of the Shetlands to the Prax Group. The reason why this is of particular interest is that the initial development of Laggan/Tormore and later Glenlivet, Edradour and Glendronach was a technology leap – a deepwater (600m) long-distance (140km) tieback with the longest pipeline network yet constructed in UK waters. It came onstream after the demise of Subsea Engineering News, but I had the privilege to write extensively about this project and to speak to TotalEnergies’ many technologists about its development. I am sure that many of the Total folk who worked on it will be wistful about passing on such an iconic project for others to produce. And in another exit, Shell and ExxonMobil are selling off most of their Dutch operation, known as NAM Offshore, to Tenaz. If Tenaz and Prax do not seem to be household names, it is not a surprise. The big companies are no longer interested in playing in the North Sea. They are taking their balls, bats and rackets and going elsewhere.